Before collecting soil in Japan I needed to test a few things. Making a radiograph, exposing photosensitive paper with radioactive materials, is more common than you might think. I’ve found many enthusiasts doing related experiments. Normally, taking an X-ray photograph requires an x-ray generator emitting high radiation to expose x-ray film in a very short period of time in order to get a clear image and to minimize the radiation exposure. But, if you use instant film, you can make a radiogram without having a darkroom, developing trays, or chemicals.

A Photogram, placing an object on photo paper to expose the shadow of shapes, requires 1/10000, or a few seconds, of exposure. And following that procedure, processing the paper takes about six minutes. With this relatively short time process, although it’s hard to get the exactly same composition each time, you can create similar compositions with adjusted exposure time or brightness of the light source. In contrast, the radiogram is a very long process because of low level falloff. In my calculations, and from my experimentation, I project that, by using the soils that I am planning to use, it’s required to expose a few weeks to a few months to get descent dark gray. And if you need to redo it to get longer exposure, you need to redo from zero again.

Experiment 1: Radioactive Isotope Disk (Cs-137)

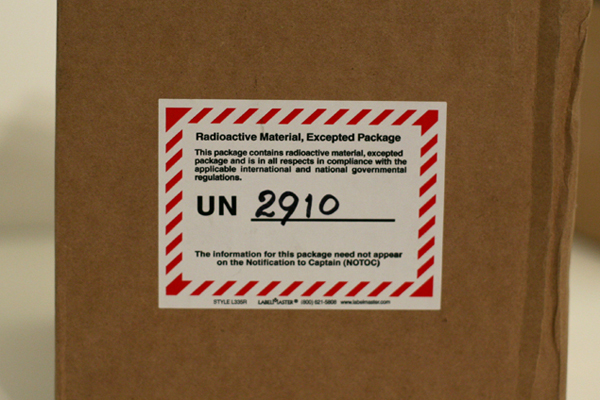

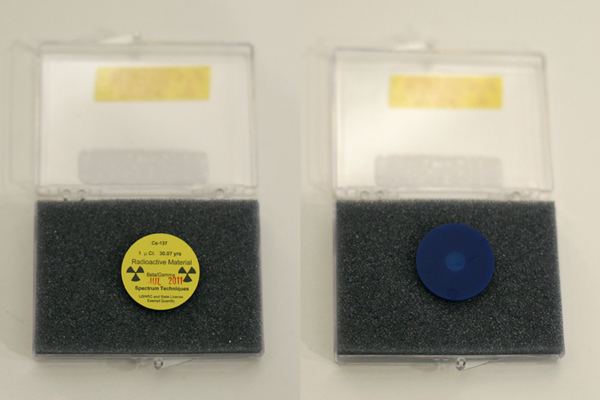

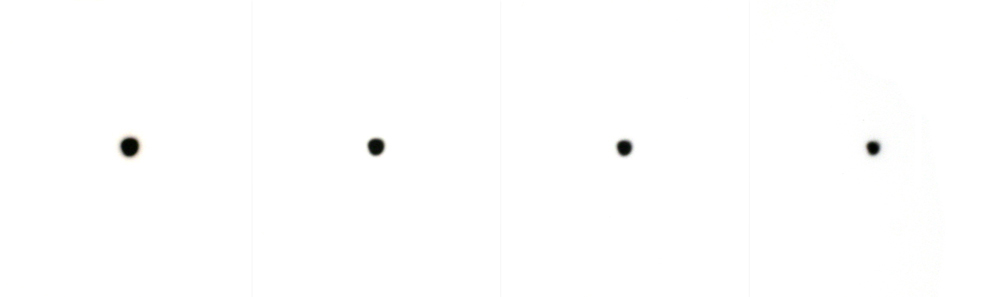

Through my research on radiograms, I found that I can purchase an exempt quantity of nuclear isotopes in a safely sealed container, for scientific or educational research purposes. I chose a Caesium 137 disk, one of the main isotopes found in nuclear fallout. The disk was “freshly” shipped from a nuclear supplier in Tennessee. It is sealed in one inch diameter plastic with epoxy to prevent leakage and contamination. I placed the disk on four layered pieces of four by five inch enlarging papers and kept them in a blackout box. A week later, I developed the papers, and the Caesium’s activity was clearly recorded. As a sheet of paper slightly blocked the radiation, the lower sheets got a smaller black dot. The geiger counter that I use for now is not the most sophisticated one, but it reflected the radiations at about 6.7μSv.

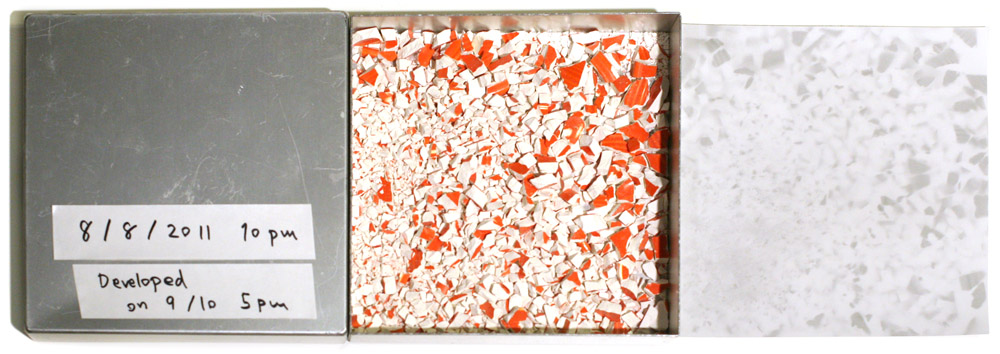

Experiment 2: Crushed Radioactive Red Fiestaware (U-235 & U-238)

Fiestaware was popular vivid colored dinnerware introduced in 1936. It wasn’t the first solid color tableware company, but it was the first widely mass-promoted and marketed in the USA. Fiesta’s re-orange glaze (1936- 43) is well-known for containing significant amounts of radioactive materials in its uranium oxide glaze. Actually, it was used widely for the red glaze produced by all U.S. potteries of the era. The use of uranium in its natural oxide form dates back to at least the year 79 CE, when it was used to add a yellow color to ceramic glazes. Yellow glass with 1% uranium oxide was found in a Roman villa on Cape Posillipo in the Bay of Naples, Italy. When 1% Uranium oxide is added into the glaze, it becomes yellow, and the more added the more orange to dark red it becomes.

This radioactive Fiestaware that I purchased is believed to contain 15% uranium oxide in the glaze, which is 0.17oz (5g) per plate in average. In 1943, the government banned using Uranium by corporations, and confiscated the Uranium of the Homer Laughlin China Co. It reminds me of Imperial Japan’s National Mobilization Law which collected all metals from citizens, including bells in Buddhist temples for war efforts. Surely, the scale is much different however.

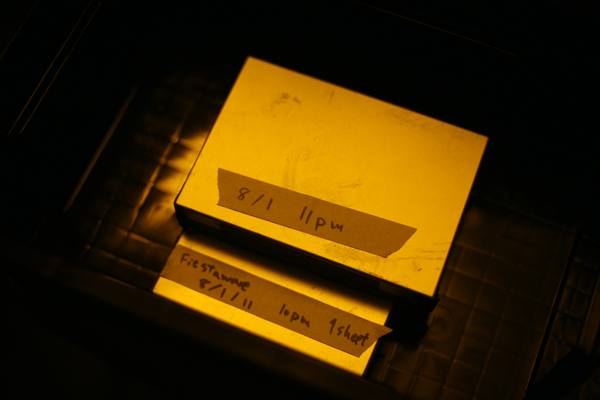

In any case, radioactive Fiestaware has been described as one of the most radioactive commercial products you could buy. For this experiment, prior to exposing photo-sensitive materials with nuclear contaminated soil, I crushed the plate to make the material more random than a single flat plate. I stored an enlarging paper with the crushed plate in a box and exposed it for a week. The exposure result was the shapes of the plate pieces outlined on the paper. I determined an even longer exposure is needed to get dark grays. As I used my geiger counter to measured this material, it indicated 1.47μSv. After a month after putting in an enclosure, the Uranium Oxide’s radiation is clearly recorded on the photo paper.